On the wall of Adam Silverman’s 5-year-old Atwater Pottery studio in Atwater Village–hanging beside Magic Marker drawings by his daughters and maps of Ibiza and Block Island–is a silver Mexican milagro in the shape of a hand. The talisman is just one of many hand-themed gifts from his wife, Louise Bonnet, which remind him of the importance of using his hands. “It’s integral to who I am,” says the potter, who also has a tattoo of Le Corbusier’s “Monument of the Open Hand” on his right forearm. “Every day I use my hands consciously, and I’m happy about it.”

Six years ago, he might not have been able to say the same. Before Sept. 11, Silverman, who trained as an architect, and Bonnet, a Swiss-born artist and illustrator, were both married to other people and involved in consumer-driven careers: Silverman co-founded the streetwear company X-Large in 1991 “on a lark,” and Bonnet was head of the cosmetics line Poole. Although each was successful–X-Large, in its heyday, had shops around the globe, and Poole sold its high-concept makeup kits at Sephora and Fred Segal–the 2001 tragedy spurred some serious reevaluation.

“It didn’t all happen Sept. 12,” Silverman says. But both eventually split with their spouses and shifted the focus of their lives to art from commerce. “I made the decision to become a full-time professional potter and not just a hobby potter,” he says, “and Louise made the decision to wind down Poole and start drawing every day again.” Now the couple has struck a blissful balance between earthy simplicity and urban sophistication.

They were married in 2004 in the Los Feliz home they share with 2-year-old daughter Prudence (whom they call Poppy) and, half the week, with Silverman’s daughters Beatrice and Charlotte from his first marriage. The house is full of friends’ artworks and exotic objects from Silverman’s globe-trotting grandmother, who took him to Ibiza, Spain, as a 10-year-old and showed him a world beyond Greenwich, Conn. And at the pair’s regular dinner parties, Bonnet’s hearty soups, farmers market salads and homemade breads are served in Silverman’s coveted handcrafted bowls.

“When we got together, I realized for the first time that eating at home could be better than eating at a restaurant,” he says, somewhat incredulously. “I remember Louise once saying, ‘I can make that better,’ and I was like, ‘Wow, you really can.'” He chuckles: “It took me 40 years to figure that out.”

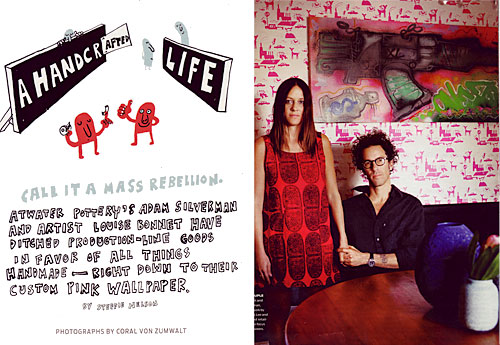

Even the dining room wallpaper, with its cartoonish pink print belying a somewhat dark Los Angeles narrative–a 7-Eleven holdup, a factory polluting the river, little angel-devil figures smoking cigarettes–was designed by Bonnet and printed at a custom shop in the Valley. “Do you know toile de Jouy?” she asks, referring to the pastoral print that was a favorite of Marie Antoinette. “I wanted to do something like that; that’s why it’s pink.”

Bonnet says her upbringing instilled in her the idea that making something by hand was a natural option–or, perhaps more accurately, the only option. “I grew up without a TV, and I had two toys,” she says. “And my mom made my clothes.” She notes that a “maroon knitted ensemble” isn’t very cool when you’re 12, but by the age of 20, she was attempting it herself. “I don’t know how to do it, really,” she insists, holding up an enormous sweater in shades of brown, gray and pink. “I can only knit rectangles . . . and it’s 3,000 pounds!”

When she’s not knitting these days, Bonnet is gearing up for a solo show in March at Shepard and Amanda Fairey’s new Echo Park gallery, Subliminal Projects. Shepard, who first saw Bonnet’s illustrations exhibited with Silverman’s pots at Silho Furniture, remembers being struck by her work’s “whimsical, ‘Yellow Submarine’ sort of feel. But it was all black and white and the iconography was of the Ramones. I thought it was a really cool juxtaposition of this fun, hippieish style with punk rock iconography.”

For the upcoming show, Bonnet, 37, will abandon her characteristic animals and imaginary figures (a past series juxtaposed innocent forest creatures with lyrics from N.W.A songs) for portraits. “I realized that I’m really interested in people,” she says, naming Picasso, Hockney and R. Crumb as inspirations. “The way Adam can make a pot for the rest of his life, even one shape, and it keeps getting better and better and better, it seems that portraits are the same sort of thing.”

Silverman, meanwhile, continues to produce upward of 800 pots a year under the Atwater Pottery banner (he is the company’s only employee). And though he refers to himself as only a potter–not a ceramist or, worse, clay artist–his evocative, elemental pieces are equally at home in art galleries from Chinatown to Japan as they are in high-end contemporary design shops such as OK on 3rd Street.

“His work is relevant regardless of context,” says OK owner Larry Schaffer, who carries Atwater creations from $125 to $1,000. “It’s esoteric and interesting. The pieces have an innate presence and, as he’s getting all this attention from the art world, there’s been this quantum leap forward in the work.”

Purposefully walking the line between ugliness and beauty, Silverman, 44, seeks out exotic glazes and kilns that leave mottled colorations, ashy residue and scars, as well as lava-like surfaces that he grinds down to expose bubbles beneath. “Anybody can make something ugly,” he explains, “and that’s not interesting. But sometimes beauty is not enough.” Silverman’s craft is based on ancient pottery techniques, but his modern yet primitive vessels provide the perfect counterpoint to sleek design, as evidenced by a chunky blue cup on the Eames table in his living room.

But beyond design and aesthetics, it’s the human touch and connection that draws people to his handcrafted objects, Silverman says. He cites an e-mail he received recently from a man who wanted to tell him how much he enjoys eating his cereal every morning from one of his bowls.

“People love coming to my studio, feeling like they made a discovery and taking home a piece of it, quite literally,” Silverman says. “Then having a pot or a bowl on the table brings up a whole different kind of discussion about these people supporting their kids’ drawing and making things out of clay, rather than, ‘I bought this chair at Design Within Reach, isn’t that awesome?’ People like that, it makes sense. And it doesn’t just connect them to us, it connects them to each other.”