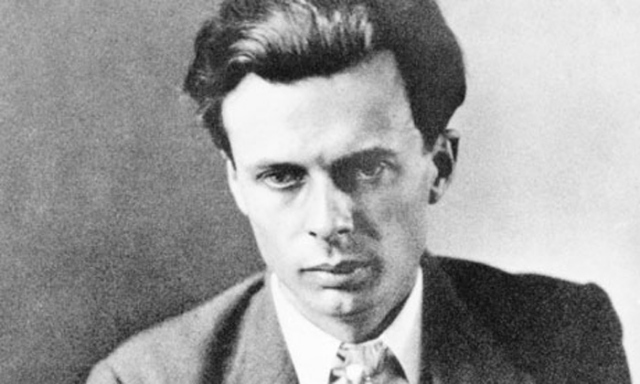

FIFTY YEARS AGO, on November 22nd, 1963, in his home at the top of Mulholland Highway beneath the first “O” in the Hollywood sign, the British author, psychedelic pioneer and visionary thinker Aldous Huxley lost his three-year battle with cancer. Per his written request, Huxley’s second wife, Laura, injected him with a dose of liquid LSD as the end drew near. She later described his passing as “the most serene, the most beautiful death.”

Earlier that same afternoon, President John F. Kennedy died of gunshot wounds in the emergency room of a Dallas hospital, and his widow could hardly say the same. So monumental was Kennedy’s grisly public assassination — even Laura Huxley recalled the nurses watching news reports about it as her husband lay dying — that its 50th anniversary has almost completely eclipsed Huxley’s in the national memory. In recent issues of Vanity Fair and The New York Times Book Review, feature articles have discussed the stacks of new books commemorating the Kennedy anniversary.

Huxley, however, hasn’t received much more than a lovely, deco-futurist illustrated edition of 1932’s Brave New World, and an assessment from two Times writers that that dystopian classic, with its predictions of 4-D interactive films called “feelies” and the habitually prescribed drug soma (“a gram for a weekend, two grams for a trip to the gorgeous East, three for a dark eternity on the moon…”), comes across today as dated, anyway.

Huxley freely admitted that the novel as a form may not have been the best container for his prodigious flow of ideas – this is an author who was contracted, during his peak years, to produce three books a year. But Brave New World’s setting in a future where control is exerted through the monitored supply of mindless, artificial pleasure sounds uncomfortably close to our present reality. As recently as 2010, it was number three on a list of books Americans most want banned from public libraries.

I would argue that it wasn’t until Huxley moved to America — specifically, to Los Angeles — that the seeds of his lifelong fascinations with technology, pharmacology, the media, mysticism and spiritual enlightenment fully blossomed and bore fruit. It’s often said “The Sixties” officially began with the death of JFK and America’s “loss of innocence.” But without the dedicated and well-documented cosmic explorations of Aldous Huxley and his cohorts, the decade would have looked very different. It’s not an exaggeration to say that, without Huxley, Timothy Leary might never have tuned in and turned on, and Jim Morrison might never have broken on through.

¤

Huxley was a poet before he became an essayist and novelist, publishing four books before 1921, when his first novel, Crome Yellow, made him a literary sensation. A satire of Bohemian British high society after WWI, it established the 27-year-old writer as a fearless social critic and an outspoken pacifist, a stance that would lead him to leave England, and eventually, Europe. From 1930 on, Huxley and his wife, Maria, and their son Matthew spent much of their time in Sanary-sur-Mer in the South of France, where he wrote both Brave New World and Eyeless in Gaza (1936).

In 1937, the family sailed to New York on the Normandie with their close friend Gerald Heard, to drive across America in a Ford sedan. They spent the summer near Taos, New Mexico, on a ranch given to D.H. and Frieda Lawrence by the art patroness Mabel Dodge Luhan. Although Lawrence had died in 1930 at the Huxley home in France — in Maria’s arms, no less — Frieda lived in Taos until her death, and the families remained close. D.H. and Aldous had forged their friendship during the idyllic Bloomsbury days; the two even made plans to start a utopian colony in Florida together. That vision never materialized, but it’s said that one of the reasons Dennis Hopper wanted to purchase Mabel Dodge Luhan’s personal Taos residence, which he did in 1970, was because of its association with Lawrence. In Hopper’s estimation, Lawrence was “the first freak.”

Huxley was a freak of a different stripe. Standing a gangly 6’4½” with an enormous head, he dressed almost exclusively in an academic’s uniform of baggy suits and often clutched a magnifying glass to help him read (he had had serious problems with his eyesight since his teenage years). The sedate Englishman, a descendant of both Matthew Arnold and the renowned Victorian zoologist Thomas Henry Huxley, didn’t exactly appear to be a poster boy for the counterculture when the Huxley family pulled up to their first Hollywood home on North Crescent Heights. However, his very publicly expressed philosophies and lifestyle choices contributed over the years to the global perception of Los Angeles as a land of heretics and hedonists, mystics and movie stars. Huxley’s role as a de facto ambassador for SoCal living did not make him very popular back in war-torn Europe — critics hurled vague insults, using words like “yoga” — but he seemed to embrace the contradictions of his new life from the outset.

The opening chapter of Huxley’s 1939 novel After Many a Summer Dies the Swan, written shortly after the family’s arrival in LA, finds British scholar Jeremy Pordage observing Los Angeles for the first time, from a car. The city’s clashing architectural styles and its people and promises come rushing at him, as they probably did through Aldous’ own eyes:

MALTS CABINS DINE AND DANCE AT THE CHATEAU HONOLULU SPIRITUAL HEALING AND COLONIC IRRIGATION BLOCK LONG HOTDOGS BUY YOUR DREAM HOME NOW!

Some claim the book was an inspiration for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, largely because of the shared characteristics between Pordage’s employer, Jo Stoyte, an eccentric millionaire who lives in a castle with his mistress and art collection, and Charles Foster Kane. The similarities end at the basic biography: Stoyte’s obsession is immortality, not power, and Huxley’s novel takes a sci-fi turn with the discovery of a 200-year-old man.

Not that Huxley was opposed to writing for the pictures, however; in fact, that was part of LA’s appeal for him. He’d become friendly with the writer and girl-about-town Anita Loos when he sent her a fan letter raving about her 1925 novel, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and she helped get him a cushy job at MGM. But unlike Loos, who’d been honing her chops since the days of silent film, Huxley’s formal style didn’t lend itself to screenwriting. One of his only produced and credited scripts was a gloomy 1943 version of Jane Eyre, starring Welles as the tortured Rochester. The dialogue is strange and stiff: “Fortune’s knocked me about, kneaded me with her knuckles, ‘til I flatter myself I’m as hard and as tough as an India rubber ball,” Welles intones, the line’s only saving grace his formidable baritone. Huxley also wrote the first draft of what ought to have been his onscreen masterpiece, Disney’s Alice in Wonderland. Unfortunately Walt personally rejected it, claiming he could only understand every third word. One of his best film credits, Ken Russell’s The Devils, adapted from The Devils of Loudon, Huxley’s 1952 nonfiction novel investigating 17th century exorcism, was posthumous.

Aside from the disappointment of not “making it” in the studio system, life in the City of Angels was treating the Huxleys well. Their intimate social circle included Heard (a renowned philosopher and mystic in his own right) and Loos, as well as Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard, astronomer Edwin Hubble and his wife Grace, fellow Brit expat writer Christopher Isherwood, and Mercedes de Acosta and Greta Garbo. It’s whispered that Garbo and de Acosta were among the bisexual Maria Huxley’s playmates in LA’s lesbian underground, and that Maria also procured young women for her husband’s enjoyment, pointing to a very wild side of the Huxleys’ private life.

It was at this time that Huxley began his friendship with Jiddhu Krishnamurti, the chosen “World Teacher” of Theosophy who’d renounced his role in the esoteric religion in 1929 but remained in Ojai, California all his life. Although he found the concept of the guru distasteful, believing that man had to be free to find his own path, Krishnamurti still lectured frequently and was revered as a teacher by many, including Huxley. He introduced the Huxleys to the practice of yoga, and impressed upon Aldous the importance of self-knowledge and free inquiry versus organized religion, with its dogma and symbols.

Along with Heard and Isherwood, Huxley also, upon his arrival in LA, became a serious student of Vedanta, the Hindu-based system of philosophy and spirituality. The three British writers studied with Swami Prabhavananda at the Vedanta Society in Hollywood, with its charming white-domed temple tucked above the 101 freeway. At the time, Heard was also creating and constructing the Trabuco College of Prayer in Laguna Beach, a center for mystical study that he funded with his family inheritance. Isherwood, on the other hand, committed himself to Vedanta so fully that he lived in the Society’s monastery and labored over a translation of the Bhagavad Gita. Huxley’s introduction to Isherwood’s translation expressed his own growing connection to mysticism, and particularly to the ancient philosophy of religion known as Perennialism. “Man possesses a double nature,” he wrote, “a phenomenal ego and an eternal Self, which is the inner man, the spirit, the spark of divinity within the soul. It is possible for a man, if he so desires, to identify himself with the spirit and therefore with the Divine Ground.” Huxley discovered that the quest for and the realization of the divinity within are themes in the mystical scriptures of all the major religions of the world, from Hinduism to Taoism to Buddhism. Thanks in large part to the library at Trabuco College, he was able to compile selections from primary religious texts and the words and writings of seers, philosophers and prophets from St. Theresa to Rumi to Meister Eckhart.

In 1945 he published his groundbreaking scholarly work on the subject, The Perennial Philosophy. In the chapter “God in the World,” Huxley looked at the Greek concept of hubris and its inevitable response, nemesis, as it relates to nature, and the Christian idea that one must return to an uncorrupted childlike state to enter the Kingdom of Heaven. “Modern man no longer regards nature as being in any sense divine,” he wrote, “and feels perfectly free to behave towards her as an overweening conqueror and tyrant.”

A few years earlier Aldous and Maria had done what so many Angelenos feel compelled to do: they moved to the desert, seeking a deeper communion with the natural world. The couple bought a cabin in Llano, next to the ruins of an old socialist colony, Llano del Rio, where Huxley tended to his garden and worked in the desert light that he believed was helpful to his eyes. Here, surrounded by vast expanses of earth and boundless sky, he experienced something infinite and undeniable. “Silence is the cloudless heaven perceived by another sense. Like space and emptiness, it is a natural symbol of the divine,” Huxley wrote in an essay about the desert. Although he was a professed agnostic (his grandfather Thomas actually invented the term, in 1869), a spark had been lit: he found himself moving ever closer to divinity.

Appropriately for a British writer with mystical inclinations descended from a line of famous intellectuals and botanists, Huxley revered William Blake, and idealized the self-taught poet and artist’s ability to exist in a visionary state where angels were as visible as humans. In The Perennial Philosophy, Huxley first quoted the now-iconic phrase from Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, warning the reader that, “the process of ‘cleansing the doors of perception’ is often, at any rate in the earlier stages of the spiritual life, painfully like a surgical operation.”

Painful or not, this was exactly what Huxley was so ardently seeking. When he heard that a psychiatrist in Canada, Dr. Humphry Osmond, was researching the biochemical similarities of schizophrenia and mescaline, a peyote derivative, Huxley contacted the doctor and suggested that perhaps the drug could also offer insights into the visionary experience. He then invited Osmond to stay with him and Maria at their home on Kings Road during a 1953 psychiatric conference, an invitation that the doctor called “an honor and an opportunity.” There was just one small request from the host: “Do you have any of the stuff on hand? If so I hope you can bring a little…”

On a now-legendary May morning, Huxley ingested mescaline for the first time, with Osmond and Maria as his guides. He admitted that he was “convinced in advance that the drug would admit me, at least for a few hours, into the kind of inner world described by Blake.” He found the “door” in an unexpected place: the casual arrangement of a pink rose, a magenta-and-cream carnation and a pale purple iris on the kitchen table. As he recalled the moment in his 1954 book The Doors of Perception:

Fortuitous and provisional, the little nosegay broke all the rules of traditional good taste. At breakfast that morning I had been struck by the lively dissonance of its colors. But that was no longer the point. I was not looking now at an unusual flower arrangement. I was seeing what Adam had seen on the morning of his creation — the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence […]

No doubt Huxley would have called the flowers “psychedelic,” had the term then been in circulation, but it wasn’t until 1957 that Osmond had his Eureka moment during a correspondence with the writer. Although the two took a scientific, clinical approach to hallucinogens, they were far from humorless about it. In trying to come up with a term for the category of drugs that includes mescaline, LSD, and psilocybin, Huxley proposed “phanerothyme,” from the Greek words for “to show” and “spirit.” In a letter to Osmond, he wrote this couplet: “To make this mundane world sublime, take half a gram of phanerothyme.” Osmond’s sing-songy response was: “To fathom Hell or soar angelic, just take a pinch of psychedelic” (Greek for “mind-manifesting”). It’s tempting to imagine them giggling and popping another tab, but that, too, would be inaccurate. Huxley was vehemently opposed to the casual, recreational use of psychedelics and only experienced around a dozen “sessions” during his 10 years of experimentation.

The years following Huxley’s first psychedelic trip were life changing for other reasons, too. In 1955, Maria, his caretaker and companion of 36 years, died of breast cancer, to Aldous’ almost complete surprise. It’s hard to feel entirely sympathetic toward a man who didn’t know his wife was terminally ill until her final week, but then, he was legally blind and she’d been determined to keep the news from him. As late as the end of January, he was writing about her “arthritic condition” in letters to Matthew and Osmond. Maria died on February 8th.

Yet for all his failings as a source of support during Maria’s illness, Aldous admirably led his wife into the afterlife, reciting to her the lessons of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, urging her to let the body go and face the Clear Light that one is said to experience at the moment between life and death. “Light had been the element in which her spirit had lived, and it was therefore to light that all my words referred,” Huxley wrote in a beautiful remembrance of her passing.

In his musings on the visionary experience, Huxley returned again and again to the image of light. In Heaven and Hell, his 1956 follow-up to The Doors of Perception, he investigated “popular visionary art” of the Romantic period such as fireworks, phantasmagorias, and magic lantern shows. He also noted that Paradise, as depicted by Dante, was “illumined as though by two suns.” No doubt the famed LA light played a part in keeping him here for so many years.

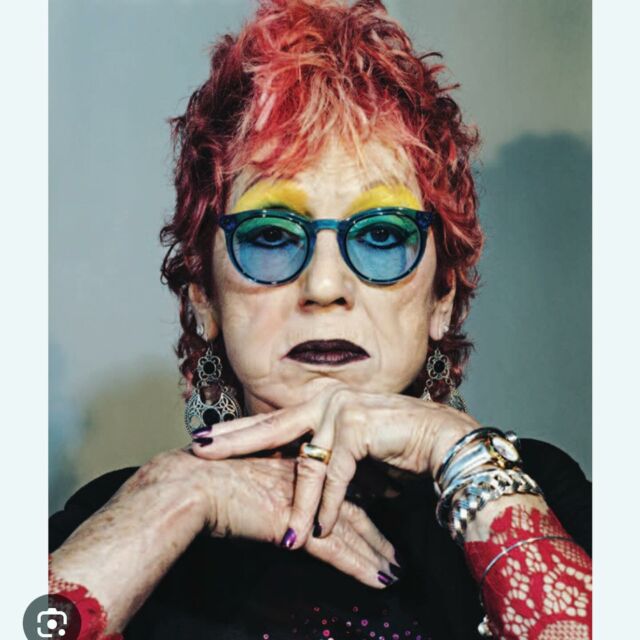

In 1956, surprising everyone including his bride, Aldous remarried at a drive-in wedding chapel in Yuma, Arizona. Laura Archera was a classical violinist and psychologist who had been a friend to both Maria and Aldous; as she recalled in her memoir of Huxley, This Timeless Moment (1968), “I have an anti-ritualistic streak in me, and a ‘drive-in marriage’ was most unritualistically attractive. Considering Aldous’s very British and Victorian upbringing, this suggestion was another revealing indication of his inner freedom.” The chapel’s ladies room attendant was recruited as a witness and the ring came from a five-and-ten, but somehow the press had still gotten wind of the wedding, and reporters were waiting outside the door. Realizing that news would spread fast, Huxley sent a letter alerting his only son, Matthew.

While Huxley’s family and old friends were alienated by the elopement, new friends had come into the fold, including Igor Stravinsky and Ginny Pfeiffer, the woman Laura had been living with before their marriage, and who many say was her lover (which, if true, would make Laura the author’s second bisexual wife). The newlyweds moved into a house on Deronda Drive in Beachwood Canyon, where Huxley began working on his final novel, Island (1962), a utopian response of sorts to Brave New World. The book is set on the remote Pacific island of Pala, a peace-loving land with untapped oil reserves where trained mynah birds remind inhabitants to stay in the “Here and now! Here and now!” Children can move freely between different families and a mushroom derivative called moksha is ritualistically consumed to help people stay connected to their “oneness.” Naturally, such a blessed state can’t last; an interloping journalist who washes ashore puts everything at risk. In a 1960 interview with the Paris Review, while he was still working on the book, Huxley revealed, “I haven’t worked out the ending yet but I’m afraid it must end with Paradise Lost — if one is to be realistic.”

All the while, the aftereffects of The Doors of Perception continued to reverberate through high and low culture. Although Huxley rejected the popular view of himself as “Mr. LSD,” his enthusiasm for the subject and belief in the transformative properties of psychedelics led him to form friendships with Richard Alpert and Timothy Leary while he was a visiting professor at MIT and they were conducting their psychedelic research at Harvard. Religious scholar Huston Smith, a close friend of Gerald Heard’s, introduced him to Zen guru Alan Watts in Cambridge as well. Huxley gave Leary a copy of the Tibetan Book of the Dead that Leary, Alpert and Richard Metzner later adapted into the manual The Psychedelic Experience, published in 1964 and dedicated to Huxley.

Shortly after his return to LA, a devastating wildfire burned his Beachwood Canyon home to the ground, destroying Huxley’s library and all his manuscripts, notebooks, family photos and letters. The author, who had recently been diagnosed with cancer of the larynx, wryly remarked to his friend Osmond that the grim reaper had him in his sights. As Laura described it, the two had been so “stunned” by the fire that they were rendered almost paralyzed. “How beautiful everything was!” she wrote. “The flames from the outside were giving to the white walls a soft, rosy glow.” A few paragraphs later she admitted that there would have been time to move some things to safety if they’d had a “friend” to help, and the Huxley family, not her biggest fans to begin with, couldn’t forgive her for this.

Luckily, Huxley did rescue the manuscript of Island, which represented five years of work. It was published in 1962 to great acclaim; The New York Times proclaimed it his “final word about the human condition and the possibility of the good society.” Reflecting on the book after Huxley’s death, Watts called it “a sociological blueprint in the form of a novel” and credited it with helping to inspire the intentional communities that flourished later in the ‘60s.

And then, of course, there were The Doors: diehard devotees of both Blake and acid who took their name from Huxley’s book, and who could probably fill more than a few psychedelic ballrooms with the fans they turned on to The Doors of Perception. Whether those readers then went on a Huxley kick we’ll never know, but for even a handful to read and think about the idea that our “goal” as humans is “to discover that we have always been where we ought to be” leaves things a little better than where they started.

There’s a sweet poetic justice in the fact that someone who so yearned to inhabit Blake’s experience and see the angels for himself, would adopt the City of Angels as his home. But LA is not Huxley’s final resting place. On the day after his death, Huxley’s body was cremated and his closest friends and family took his daily walk around the Hollywood reservoir, but there was no service. Then, in 1971, his ashes were returned to England and interred in the Huxley family grave at the Watts Cemetery in Compton, Surrey. It’s said that the site is neglected, but hopefully on this anniversary some English acolyte will take a moment to brush off the leaves, clear away the weeds, and maybe even lay a little nosegay that contains nothing less than the miracle of naked existence.

¤