Theresa Duncan worked hard to get out of Lapeer, Mich., where she was born in 1966, and where, last month, she was buried. On her blog, the Wit of the Staircase, the writer and filmmaker compared Lapeer to the small Texas town in Peter Bogdanovich’s “The Last Picture Show.” “You would think it was 1951,” she wrote, adding that her birthplace was “similarly subject to incredible boredom punctured by baroque social intrigue.”

Another post recalled a long ago summer day and Duncan’s turn down the literary path: “At the quarry in July my cousins told me the water was ‘bottomless,’ and so I hugged the shore and learned to swim in the Lapeer library instead, suspecting already exactly what the limitless meant. . . . Ever after I knew all the haunted shades of meaning that were captive in other people’s words. And for that they called me mad.”

It’s a label that has followed her to the grave. Many newspapers have reported on the double suicide of Duncan and her artist boyfriend, Jeremy Blake, in New York, trying to understand the deaths of this “golden couple” (who lived in Venice until February) with accounts of paranoia, mental instability, codependency and professional disappointments. The reports noted Duncan’s success as a creator of CD-ROM games for girls as well as the setbacks she experienced more recently with several feature film projects.

Few, however, gave more than a passing mention to her blog, which she launched in July 2005 and typically posted to three or four times a day.

Lavishly illustrated with fine art, fashion photography, film stills, news and paparazzi photos, book and album covers, and recurring images of Kate Moss, her preferred celebrity obsession, Wit, as she called it and herself interchangeably, was a cultural free-for-all. In this forum, which she could credibly assert was engendering a new type of writing, Duncan shared the things that caught her fancy, sometimes crafting lengthy, heavily researched ruminations on subjects mundane and arcane, sometimes excerpting articles or posting poems or even listing a particularly good run on her iPod. Always, her poetic sensibility, arch glamour and fiery spirit came through. Hers was a unique female voice, and this is why her death is such an acute loss to her readers, myself included.

Duncan portrayed herself as a Freudian and a fashionista, an intellectual and a stoner, a political radical with a perfume fetish, and a groupie in a 12-year monogamous relationship. Because of the pliancy of her mind, these seeming contradictions could coexist. She was hungry for knowledge, for answers, for beauty, and she created an online space that was essentially a map of her discovery process — a “web log” in the truest sense. Wit dug deep, and through her I first learned about the German groupie and left-wing sex symbol Uschi Obermeier, the heiress, social activist and literary muse Nancy Cunard and the L.A. artist and occultist Cameron. Maybe it was just her knack for self-mythologizing, but Duncan seemed connected to the lineage of freethinking women she wrote about.

In her posts about Detroit — to which she was as devoted as she was ambivalent about Lapeer — you can trace the roots of her radical sensibility. Duncan lived in Detroit — birthplace of the automobile and the Stooges and the MC5 — in the late ’80s, and going back for a recent visit she even found magic there in bitterest winter, standing with a friend on the roof of an abandoned building downtown. “He said, ‘I can breathe your name, every letter shaped perfectly.’. . . They all came out just formless clouds, but he spelled my name out over the city of Detroit, and that’s an incantation all its own.”

Perfume was another of Duncan’s passions. Six days before she died, she wrote about a scent called Aria di Capri, comparing it to “a beautiful woman’s laugh, startling, sharp and silver like a 747 slicing suddenly above the cloud cover and rising into the sun.” Scent could conjure her parents’ moonlit frontyard; Talitha Getty’s Marrakech; clothes by Ossie Clark and music by Joni Mitchell; or “the house you never go in by the beach with the crooked Christmas lights and dirty pink and blue and yellow lawn statues where the old hippie lady smiles sometimes from the porch, and sometimes curses and raves and moves in circles around the yard.”

Asked in an interview with LAist to imagine a perfume version of Los Angeles, she described a blend of “celluloid and sand, coyote fur and car exhaust, contrail cloud and chlorine, bitter orange and stage blood and one bushel of ghostly, shivery night-blooming jasmine flowers like blown kisses from the phantoms of the ten thousand screen beauties who still haunt our hills every full moon because they think it’s a stage light.”

Duncan was intrigued by beautiful, thwarted women: starlets who never quite reached icon status, like Tuesday Weld, and it can’t be said that she wasn’t, to some degree, interested in suicide. She asserted that Jean Seberg was driven to suicide by the FBI. She posted photographs by Francesca Woodman, the beautiful self-portraitist who jumped out a window at 22. Hunter Thompson’s suicide note, she informed us, was titled “Football Season Is Over.” She also posted poems by Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton and Sarah Hannah, a Boston poet who took her own life this May at age 40.

While she often commemorated the birthdays of her heroes (Thomas Pynchon, Sigmund Freud, Franz Kafka, Kurt Cobain), Duncan’s own 40th birthday, Oct. 26, 2006, went unmentioned. However that day she linked to a report of an “extraordinary, enchanted masked ball” held in London (naturally, Kate Moss was there), which she proclaimed “almost as strange and wonderful as one of the Los Angeles Lunar Society’s monthly full moon meetings.” Some of her most fantastical writing could be found in her posts about this imaginary secret society of artists and filmmakers, of which she was “head librarian.”

A love affair with L.A.

DUNCAN cultivated an aura of glamour and cool, and part of it seemed to stem from her association with Los Angeles, a city she adored. “Landlocked for decades and then free at last,” she wrote about the first time she saw the ocean. Soon she was writing paeans to Abbot Kinney, Malibu Barbie, Beverly Hills and the Santa Ana winds. With her Art Luna-highlighted hair streaming behind her, she crossed town in an Alfa Romeo convertible, drinking Manhattans at the Chateau Marmont and blogging every Tuesday afternoon from a poolside cabana at the Viceroy Hotel — or so she said. But when she and Blake broke their lease in February and moved to New York, she only casually referred to “relocating editorial offices,” not mentioning their new home in the rectory of St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery until April. What happened to the love affair with Los Angeles? For one thing, Blake had been hired as a designer at New York-based video giant Rockstar Games.

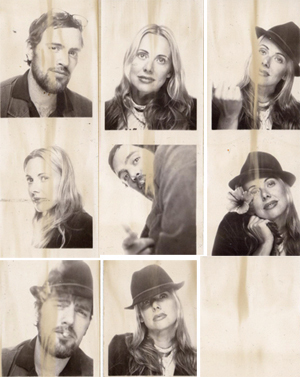

Duncan gave the impression that she was settling into and even relishing her East Village life. A June 14 post included photographs of her and Blake painting the town “rouge” and announced that they were accepting “all radical chic invitations.” Then she alluded to the harassment they were supposedly victims of. (“Beneficiaries?” she mused cheekily.) Was her flip attitude a smoke screen, meant to disguise that Wit’s world was crumbling? It didn’t seem that way. The day before she died Duncan posted a link where you could find out what tarot card corresponded with your name; hers was the empress.

I didn’t know her, and it’s impossible to tell from reading the Wit of the Staircase to what extent Duncan and Blake might have alienated their friends or burned their bridges toward the end. Her writing was always opinionated and often arrogant. She routinely skewered the establishment (Artforum, she said, was a “fading critical powerhouse”) and went after her perceived enemies, including the U.S. government, with claws out.

But none of this explains why she’d swallow a bottle of Tylenol PM (if I had to, I would have wagered on an asp to the breast).

The last post is a searching tribute to Duncan and Blake from their friend Glenn O’Brien. According to Raymond Doherty, a friend of Duncan’s who is now maintaining the site, “the plan is to keep it up forever.”

Yesterday I came across a post from Sept. 27, 2005, illustrated with a photograph of Duncan and Blake together on a couch in their Venice cottage. Duncan was kneeling, facing Blake and holding a stethoscope to his chest. She explained that they’d been chosen by an artist who was collecting sound recordings of “lovers’ heartbeats” and that the photograph was taken as she recorded Blake’s. Duncan described the experience as “amazing, like staring through a telescope at a vast and previously undiscovered world. The beats sounded so powerful, and yet so temporary,” she wrote. “We are just another damn song.”