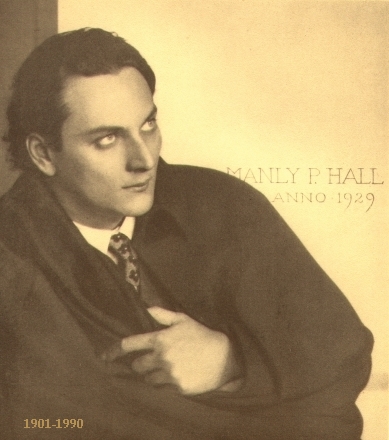

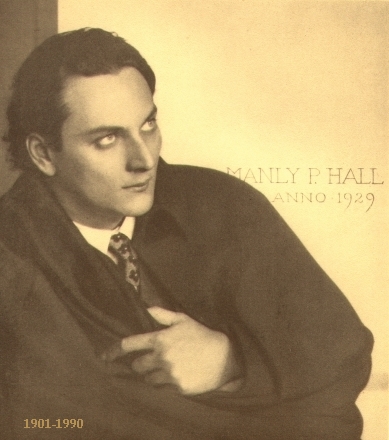

Last Sunday evening at the Silent Movie Theater, a clip from the 1938 astrological murder mystery “When Were You Born?” was shown as part of an “Occult L.A.” program curated by the author Erik Davis. In the clip, legendary occult scholar Manly P. Hall, who had also written the movie’s script, appeared on screen to introduce the concept of astrology. With penetrating blue eyes, thick dark hair and a rakish mustache, Hall had the looks of a silent film star, and he radiated intensity as he explained the various personality traits of the different sun signs — Leos are loyal, Capricorns are brave, and so on. But that’s not all: “Astrology can solve crime!” he exhorted. “It has solved many crimes in the past.”

The film was a bomb, but the fact that this obscure clip was being screened before a sold-out crowd of artists, intellectuals and spiritual seekers shows that the cycle of Hall’s influence continues. And it may grow in the coming months, for Process Media has just published “Master of the Mysteries,” the first biography of Manly Palmer Hall, written by Louis Sahagun (who is a staff writer at The Times).

In his lifetime, Hall befriended notables as disparate as Bela Lugosi and John Denver. For his writings alone he was made an honorary 33rd-degree Freemason (the highest honor), and even Elvis was a fan, sending Priscilla Presley to one of the world renowned orator’s lectures because he was afraid of getting mobbed himself.

Hall died in 1990 at age 89, and it wasn’t until a few year later that Sahagun, who’d written his obituary, began to delve deeply into his history and body of work — which includes more than 200 books, most notably his magnum opus, “The Secret Teachings of All Ages.”

“It turned out he was a pretty darn good writer,” Sahagun said. “His books were strange and absolutely fascinating, and his whole raison d’etre was applying ancient philosophies to solve modern problems. . . . He wanted to be the high priest, the hierophant, of Southern California.”

The year Hall arrived in Los Angeles, 1919, was the year the city started to boom. “It’s a fascinating parallel,” Sahagun said. “Southern California in general was the last best place, a place of new beginnings.” To Sahagun, Hall’s journey was “the spiritual equivalent of the California dream,” and when he decided to write “Master of the Mysteries,” he wanted it to be as much a history of mystical Los Angeles as a biography.

Jodi Wille, the editor of “Master of the Mysteries,” said, “I learned so much working on this book. Not only was Manly P. Hall this incredible thinker, but Los Angeles was this remarkable city run by wild bohemian visionaries who were totally tuned in. It makes me just want to turn everybody on to it so we can know what our real roots are. Our roots are not Britney Spears.”

A junior high school dropout from a broken home, Hall was regarded by many as a magician, but to Sahagun he was really a “one-stop scholar of ancient ideas.” One of Hall’s first friends was Sydney Brownson, a phrenologist with a booth on the Santa Monica Pier, who shared his knowledge of Hinduism, Greek philosophy and Christian mysticism. Hall, who had a photographic memory, furthered his studies of ancient religions and soon was speaking at the Church of the People downtown. By 1920, only 19 years old, he was running the church and delivering Sunday lectures about Rosicrucianism and Theosophy, the mystical philosophical system founded by Madame Helena Blavatsky; as well as the teachings of Pythagoras, Confucius and Plato.

And he was not addressing some fringe contingent. At this time Los Angeles was alive with esoteric ideas and populated by spiritualists with names like Princess Zoraida and Pneumandros. As Sahagun put it, “Even flamboyant holy roller Aimee Semple McPherson, who arrived in Los Angeles in 1918, was milquetoast compared to others setting up religious shops in town.”

Hall became the beneficiary of Caroline and Estelle Lloyd, a wealthy mother-daughter duo from Ventura, and in 1923 their generosity enabled a trip around the world that would provide the inspiration — and the information — for his encyclopedic masterwork, “The Secret Teachings of All Ages.” The publication of this lavishly illustrated, oversize text, which sold for $100 in 1928, turned Hall into an icon — no doubt partly thanks to the dramatic portraits done by his friend William Mortensen, a Hollywood cameraman who had also photographed Jean Harlow and Cecil B. DeMille.

In 1934, Hall founded the nonprofit Philosophical Research Society. He purchased a plot of land near Griffith Park for $10 and commissioned architect Robert Stacy-Judd to design a Mayan-inspired center with a library and auditorium, which is still active today. A plaque in the courtyard, near where the current Sunday lecture schedule is posted, reads, “Dedicated to Truth Seekers of All Time.”

Yet for all his mental discipline, Hall was in terrible physical shape, with great folds of sagging flesh around his middle (Sahagun describes him as “avocado shaped”). According to Sahagun, Hall, when asked what he would wish for if he were given one wish, said that he would like to be placed in a swimming pool full of chocolate pudding so that he could eat his way out.

Nor did his vast knowledge help his personal relationships. Hall was married twice, the first ending with his wife’s suicide; the second, almost 20 years later, was to a woman who was emotionally abusive and was classified by the FBI as a certifiable nuisance. Both marriages were childless. Sahagun doesn’t believe Hall’s second marriage was ever consummated, and there were rumors that he might have been gay. Whatever the case, this was a man who lived primarily in the world of books and ideas, and also one, it’s important to note, who had always warned of the dangers of putting spiritual leaders on a pedestal.

“All followers who offer to adorn and deify their teachers set up a false condition,” Hall wrote in a 1942 essay. “Human beings, experience has proved, make better humans than they do gods.”

“That sets him apart from, say, a Deepak Chopra, who titles a book ‘Defying the Aging Process,’ ” Sahagun said.

Sadly, Hall and Los Angeles grew out of step with each other. His work might have been “the very soil that grew stories and myths like ‘Star Wars’ and ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark,’ ” but by the time George Lucas came along, Sahagun noted, “Manly’s trove of ancient notions just seemed so dusty and out of touch.” (Not so today, when Tarcher Penguin’s 2003 reissue of “The Secret Teachings” is already in its 16th printing.)

In the ultimate, final tragedy, this man who believed in reincarnation and who had planned to leave the earthly plane consciously, might have been the victim of a greedy plot devised by his assistant Daniel Fritz, who rewrote Hall’s will. Hall’s body was found under suspicious and horrifying circumstances, apparently dead for hours and with thousands of ants streaming from his nose and mouth. The case was never solved.

Not surprisingly, this was the beginning of a low point for the Philosophical Research Society, which sold rare alchemical texts to the Getty to pay for some of the legal fees incurred by Hall’s widow.

Today, however, the center is on an upswing. In 2002, the society formed a distance learning university, offering a master’s degree program in consciousness studies, with faculty including Jonathan Young, a protege of Joseph Campbell, and Vesna Wallace, a professor in the religious studies department of UC Santa Barbara. This January, the university received national accreditation. The library, featuring some of the rarest philosophical, religious and occult texts in existence (books on black magic and Satanism are stored under a Buddha to balance the energies), remains open to the public every Saturday and Sunday.

“People are hungry for the material,” said society librarian Maja D’Aoust, who co-authored the alchemical primer “The Secret Source” with Adam Parfrey and lectures most Sundays.

D’Aoust conceded that some might find the prospect of thumbing through 30,000 volumes intimidating, and she suggested just starting randomly. “There are very interesting synchronicities surrounding the research that happens in this building,” she noted. “Just pick a book, any book. Even if you don’t know what you’re looking for, it will probably find you.”