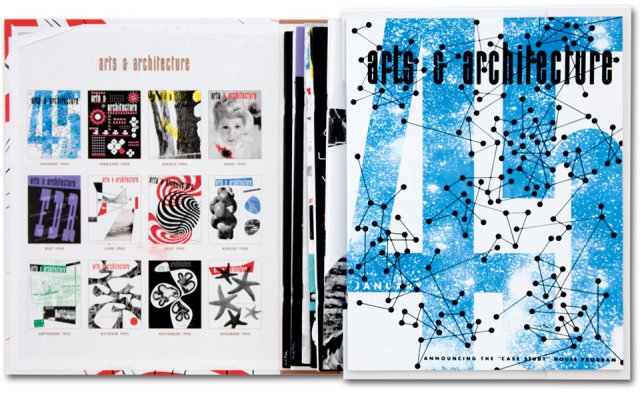

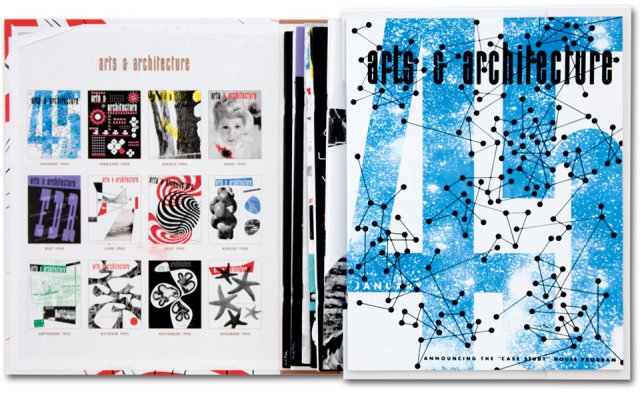

Its pages may espouse the principles of modernism and minimalism, but in its presentation, Taschen’s Arts & Architecture, the Complete Reprint 1945-67, is as maximal as it gets – in the publisher’s standard fashion. After distilling seven decades of the Italian design journal Domus into 12 hardbound volumes, Taschen took a different approach with A&A, the legendary L.A. magazine which launched the Case Study House Program and essentially codified the California modern aesthetic. In a limited edition of 5000 they’ve reproduced every issue of the magazine from editor John Entenza’s announcement of the Case Study program in January 1945, until publication ceased in 1967. The first installment, covering 1945-54, is in stores this month (the second follows in 2009).

This ten-box set of 118 magazines, complete with ads, is a true gift to lovers of modern architecture and design, for copies of the small print-run Arts & Architecture are scarce to nonexistent today. “And by God if they didn’t get every one!” exclaims David Travers, who edited A&A from 1962-67 and wrote an introduction to the collection. “The CIA couldn’t have done better,” he adds with a chuckle.

Just assembling the collection was a two-and-a-half year process, says Taschen’s managing editor Nina Wiener. Most came from private collectors in Los Angeles; about a third were in the archives of photographer Julius Shulman, who began working for A&A in 1938 and photographed 18 of the 25 completed Case Study homes. Although Shulman, now 97, has been outspokenly critical of Entenza’s choices of Case Study architects (some of whom, he argued, were not pioneers in low-cost housing at all), he says the collection represents “a tremendously significant treatise on the history of modern architecture – where we’re going and where we’ve been.”

In addition to championing the now-iconic work of Richard Neutra, R.M. Schindler, Eero Saarinen, Charles and Ray Eames, John Lautner and Pierre Koenig, and being the first to publish Frank Gehry and Richard Meier, A&A also covered modern art – devoting pages to Ad Reinhardt and Isamu Noguchi – and music. Its graphic, abstract covers were “touched by Dada,” writes Travers in his introduction, and the magazine’s logo, it was recently learned, was designed by Alvin Lustig, famed for his New Directions book jackets. As Wiener notes, some of the most colorful graphics in A&A’s pages were in advertisements for Knoll and Herman Miller. “There’s a lot of insider information there for cultural archivists and historians,” she says, but also for fans of the Case Study House program who want to delve deeper into the philosophies that drove that program and informed the editorial direction.

Travers characterizes Arts & Architecture as “hopeful about life”; Entenza’s monthly “Notes in Passing” typically ruminated on how to address larger issues like illiteracy and human rights, and unlike today’s home design magazines the bulk of its pages were truly devoted (at least in theory) to the average American family. Of course, architects and their egos are no new phenomenon, but as Travers observes, “in those days it seemed that it was tempered a bit by a social concern.”

Wiener shares the former editor’s hope that exposure to A&A’s ideas might somehow nudge society in a more positive direction. “If we could get back to a simpler way of living we’d all be better off,” she says, shrugging. “Maybe that’s just romanticizing the past, but I’m all for it.”