In 1974, a book called The Faith of Graffiti, featuring photographs by Jon Naar and an essay by Norman Mailer about a new art form rising from the streets and subways of New York City, found its way into the hands of a student at l’Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Nantes, France, named Marie-Paule. A seminal document of the graffiti movement —”screaming through space on a unilinear subway line,” as Mailer described it—the book had such an impact on the young artist that for her final project of the year, she built a wall of bricks and cement, and invited her fellow students to tag it.

Two years later, the daughter of a military officer who spent her early years in Morocco had quit art school, said goodbye her family, and moved to New York with her photographer boyfriend, Edo Bertoglio. The plan was to stay for six months, but she never left—finding herself at the epicenter of a seismic cultural shift that she would faithfully document with her Polaroid camera. At first the couple lived uptown, on 84th Street between Central Park West and Columbus Avenue, and Maripol (a spelling she created and changed legally, to help Americans pronounce her name) used to spend hours at the nearby 86th Street subway station, sitting and watching the number 5 express trains go by. “For me it was like looking at a painting,” Maripol recalls during a recent interview in Los Angeles, her French accent still heavy. “Back then, the trains were covered [in graffiti] inside, outside, the windows…you wouldn’t even be able to know your stop! And when it’s going that fast, you’re talking about abstract art.”

But it was also, she points out, a tool of communication in an era before cell phones or the internet, a way for kids in the projects in Harlem or the Bronx to literally make a name for themselves in the glittering city below—even if it was just their tag rushing by on a train car. The late seventies were a time of exceptional lawlessness in New York City, which made it fertile turf for artists and the young. The city was on the brink of bankruptcy, and President Gerald Ford notoriously refused to offer aid. “We were in the hands of God knows who—the Mafia, probably,” says Maripol. “And that’s when I landed in New York, so of course it was paradise, you know?” She smiles.

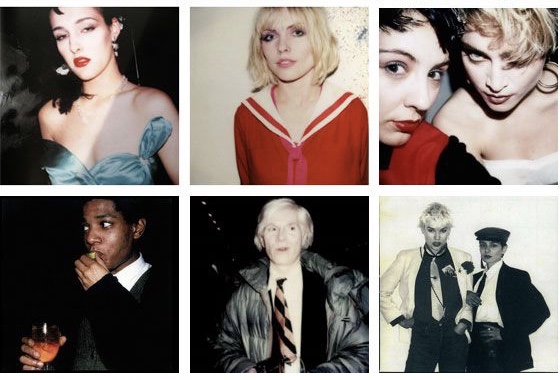

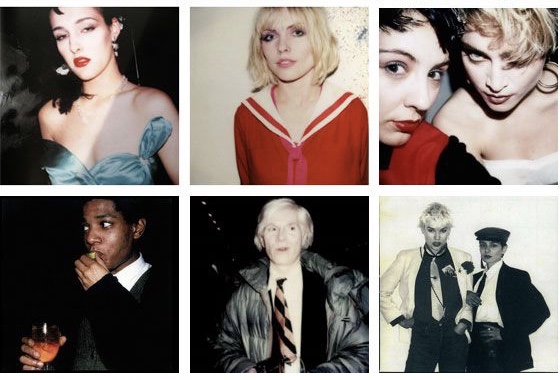

Lofts were cheap, and worlds were converging and inspiring each other: uptown/downtown, black/white, gay/straight. The editor, raconteur, television host and dandy Glenn O’Brien, who passed away in 2017, was the couple’s first friend. He was also an early staffer at Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, and two of the major social hubs of that scene were the iconic disco, Studio 54, and Fiorucci, the retail store-meets-gallery-meets-nightclub that epitomized the era with its fabulously flashy mash-up of glitter and graffiti, tinged with new wave neon. In 1977, Maripol received her first Polaroid camera as a Christmas gift from Bertoglio, and the film’s instant technology and blown-out, saturated hues made it the ideal format to capture her colorful crew—which included, over the years, everyone from artists Kenny Scharf, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat to FAB 5 FREDDY, Debi Mazar, Deborah Harry and Madonna, whose iconic early look she helped to create. “I feel lucky because I’m an archivist. If I did not take my Polaroid everywhere I wouldn’t have anything. My boyfriend had a Hasselblad and major equipment, and you did not take that to a club.”

Even back then, the film cost nearly a dollar an image, leaving little room for error. “Do you ever see me shoot two pictures of the same thing?” asks Maripol rhetorically, by way of explaining how she—a “poor artist”— could afford this expensive habit. “I shot very little. I was always very sure of my shot—the lighting, the composition.” This was long before corporate sponsorship was an art world buzz phrase, and she would seek out spots on Canal Street to source discount film. Sometimes, if an image wasn’t up to par, Maripol would draw or paint over it. Unlike many of her artistic peers, she was also a working woman, first as an assistant to the photographer Jean-Paul Goude, Grace Jones’ longtime partner and collaborator, and then as a stylist. She is credited with styling the cover of Blondie’s Parallel Lines album in 1978, but, she said, “they didn’t let me do much.” The same year she co-starred with John Lurie in Becky Johnson’s short experimental film Sleepless Nights.

Around this time, Maripol met Jean-Michel Basquiat. “I can never pinpoint the exact moment,” she said. “It could have been on Glenn O’Brien’s [cable access show] TV Party, it could have been at the Mudd Club. Basquiat used to deejay and then take his records and throw them.” But before she met the person, “I met Jean-Michel as SAMO, as a poet of the street,” Maripol says, referring to the surreal, political verse in blocky spray paint lettering that was Basquiat’s signature at the time. She and O’Brien developed an idea for a film about a young artist much like Basquiat, living and working and leaving his mark on the streets of the East Village and the Lower East Side. This became the near-verite time capsule Downtown 81, which Bertoglio directed. Basquiat turned 20 on the set, and a star, of sorts, was born.

The 1981 New York/New Wave show curated by Diego Cortez at PS1 made a formal connection between rap and graffiti culture out of Harlem and the Bronx, and the downtown club culture that brought punk and new wave into the mix. The work of graffiti writers like Lee Quinones, Zephyr, Lady Pink and Basquiat was exhibited for the first time, with Maripol’s Polaroid portraits putting faces to the names. From that point on, this group’s influence continued to expand and overlap with other circles. “I remember seeing The Clash at this club, The World,” Maripol recalls, “and Futura was doing live painting with them. That’s rocking the casbah, right?” She would later serve as godmother to Futura and CC’s child, with FAB 5 FREDDY as the godfather.

The sensation that was Madonna marked the moment the downtown underground broke through for good. Maripol, then the artistic director of Fiorucci with her own jewelry line, was called upon to revamp the burgeoning pop star’s look before the release of her 1983 debut album. Maripol stacked rubber bracelets and rhinestones on the singer’s wrists, put crosses around her neck, and soon Madonna (who was dating Basquiat at the time) was dancing around with a can of spray paint in the video for “Borderline.” Unfortunately, the look spawned so many “wannabes” that companies started reproducing her jewelry, including the rubber bangles that Maripol conceived as a “message of peace,” inspired by soldiers in Lebanon who would tie their guns with the rubber gaskets. Eventually, she says, “I had to close my gallery store and my company because of the fact that I was copied all over the world.”

Maripol went on to design other jewelry collections, most notably a recent collaboration with Marc Jacobs, and she published several books of her work including 2005’s Maripolarama, but today the fate of her physical archive is her greatest concern. She realizes some art patrons might regard the idea of going out all night and snapping instant photos—including, she claims, the earliest documented “selfie”—as frivolous, but she is certain of the importance of her role. “I approach my relationship to art like Proust,” she says. “I observe society; I take photos of it…It needs to be preserved.” Many of her subjects are now dead, and in most cases—with the exception of large format black-and-white Polaroid film—there is no negative, just a single original print. The emulsion of the eighties images, shot on first generation SX-70 film (Polaroid technology has been bought and sold several times over in the last two decades) remains fixed, thanks in part to her obsessive maintenance of a temperature controlled environment. Now she is looking for an institution to take over the job, with the goal of keeping the collection together.

Encouragingly, several major museum shows have honored the culture of No Wave New York in the last year alone, with Maripol’s contributions recognized along with it. In 2017, MoMA screened Sleepless Nights as part of an exhibition about Club 57, another cultural flash point, and the Jean-Michel Basquiat retrospective Boom For Real at the Barbican in London featured a wall of Maripol’s Polaroids. She is also regularly commissioned by couture houses including Dior and Valentino, to bring her uniquely graphic and sexy portrait style to their look books and advertising campaigns.

If Maripol possesses a rare gift beyond her impeccable eye, it is her ability to stay in the present and trust her destiny, as she did so many years ago as a young art student. “I don’t have any regrets,” she says. “I like the fact that I stay true to myself, and I try not to sell myself.” Although her ties to New York remain strong, she notes sadly that the city she knew in the late seventies has “lost its soul.” Still, she is unwilling to succumb to bitterness or nostalgia for times past. “I don’t think it’s fair for the young generation, because there is always going to be a wonderful new writer, designer, artist.”

Lately, Maripol has been spending a lot of her time in Los Angeles, where the art world is thriving and friends like Kenny Scharf and her son Lino Meoli live—although as a deejay, artist and photographer, her son is, fittingly, often traveling the world. Her plan is to make “new art, new films, new everything”—and chances are she will be at the center of a dynamic scene someplace where the underground is alive and well.