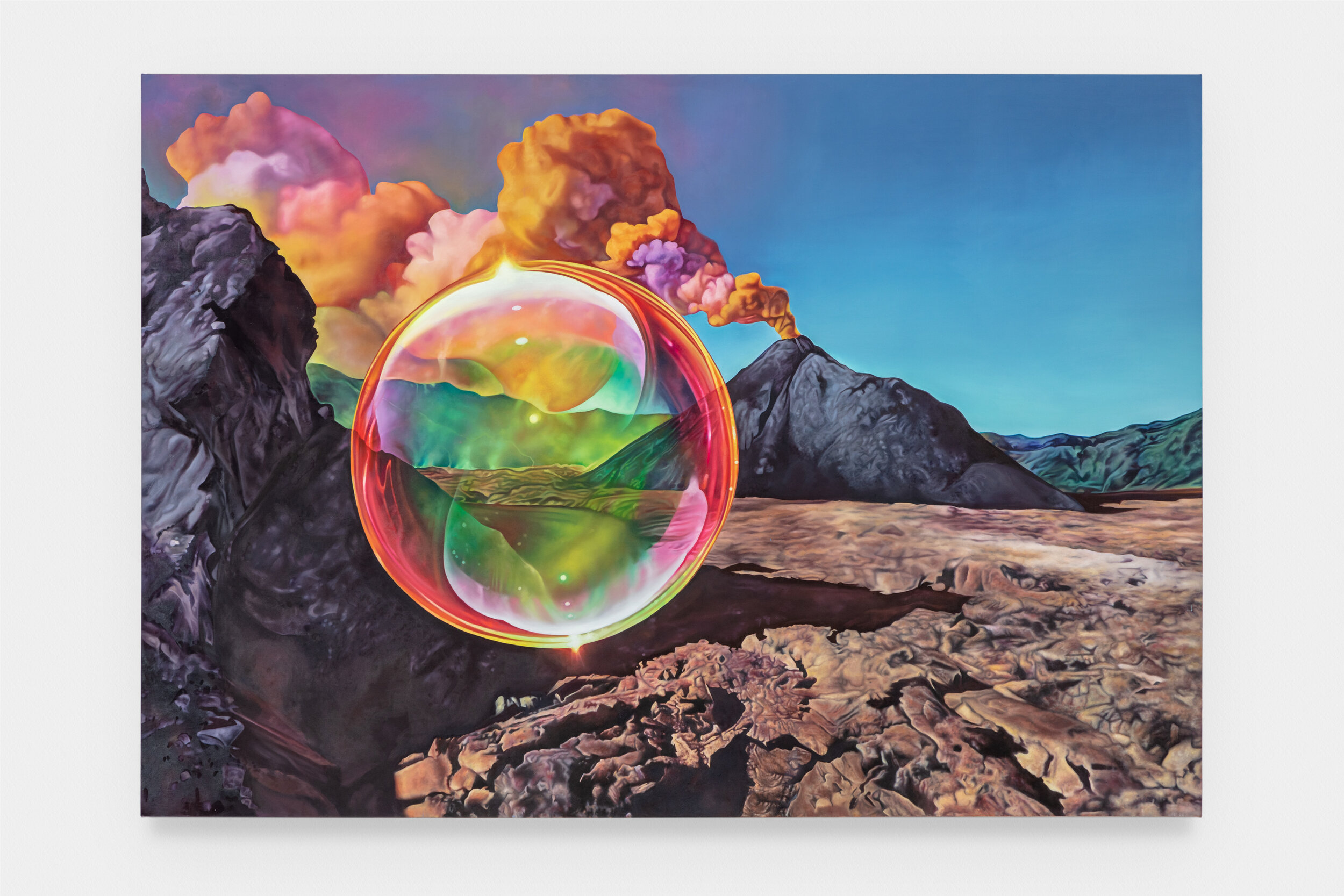

Ariana Papademetropoulos. “Origins” (2021). Oil on canvas. 84” x 120”. Courtesy of Ariana Papademetropoulos and Jeffrey Deitch Los Angeles.

Ariana Papademetropoulos. “Origins” (2021). Oil on canvas. 84” x 120”. Courtesy of Ariana Papademetropoulos and Jeffrey Deitch Los Angeles.

The artist Ariana Papademetropoulos moves effortlessly between dimensions. With her recent show, The Emerald Tablet, she took us over the rainbow. In this interview for Flaunt, she spoke about how she got there.

The paintings of Ariana Papademetropoulos are portals—prismatic dreamscapes in which floating bubbles contain other worlds, mythical beings and mysterious lights appear, and gems and flowers gaze back at us. With The Emerald Tablet, a solo exhibition and curatorial project on view at Jeffrey Deitch Hollywood through October 23, the gallery itself has become a portal. Featuring five large new paintings by Papademetropoulos plus works by 25 other artists, The Emerald Tablet is inspired by LA’s identity as a nexus of fantasy and spiritual seeking. Theosophy, the esoteric system that flourished in early Hollywood and has resurged with the recent rediscoveries of the artists Agnes Pelton and Hilma af Klint, is threaded throughout.

Papademetropoulos named The Emerald Tablet for the ancient alchemical text that inspired the Emerald City in The Wizard of Oz—whose author L. Frank Baum was a Theosophist. Taking cues from this foundational LA myth, the native Angeleno leads viewers on a visual journey that subtly mirrors Dorothy’s own. Raúl de Nieves’ bejeweled carousel, “When I look into your eyes I see the Sun,” whirls us into another realm, leading to encounters with, among many characters, a monstrous red witch by Jordan Wolfson, and Isabelle Albuquerque’s “Orgy for 10 People in One Body no. 8,” a sylphlike feline clad in human hair whose pose nods to Andrew Wyeth’s wistful “Christina’s World.”

The show culminates in Papademetropoulos’ version of the Emerald City—where utopian visions reflect and play off one another. Mike Kelley’s mystical metropolis “Kandor 18B” dialogues with the luminous, cathedral-like shapes in four Agnes Pelton paintings, and an ethereal soundscape by Beck occasionally intersects with the voice of Uriel, the leader of the interplanetary art collective, Unarius, whose 1982 film “Crystal Mountain Cities” plays on a loop. Papademetropoulos’ goal is to lead viewers back to themselves, toward what she calls “the inner reaches of outer space.”

On the eve of a recent trip to Paris, Papademetropoulos invited us to climb inside her “rainbow hole”—which is in fact a simple and accurate description of the vividly colored, carpeted office nook she carved from a corner of her Mount Washington art studio—to talk about the interplay between art and spirit, fantasy and reality, and the path that led to the creation of her “dream show.”

🌈

SN: What was your early art practice like? What were some of the first things you made where you thought, ‘this feels really good?’

AP: When I was 15, I started painting a lot of things that were a bit cosmic and between dimensions. And I started getting interested in the threshold of a painting, blurring worlds into one another. I have a painting I made when I was 15, and it’s huge—it’s like six feet—and it’s all of these naked girls in a cave.

Wow, so you have carried that vision since day one!

Yeah, and then when I went to CalArts, I changed my practice. I made my paintings ‘secretly magical,’ as I called it, but I felt like I had to tone things down a bit. And then this last year, during the pandemic, I said okay, what if these are the last paintings I ever make, what do I really want to make? What are honest paintings?

Do you have an active spiritual practice or is painting your spiritual practice?

I would say that painting is my spiritual practice, but I’m interested in esoteric subjects. I’m not in any way a scholar, but I explore topics. That’s why I’m very drawn to these female spiritualist painters—Paulina Peavy, Agnes Pelton, Hilma af Klint. I feel like I’m connected to that line of painters who work from a place of intuition.

They also use their art for personal transformation. When did you recognize that art making could be transformational?

I feel like I’m still discovering that. Recently I’ve been thinking about painting because it’s like the most traditional way of making an artwork, and yet we always go back to it. So I’ve been thinking about why that is; why do we go back to painting? And I think it is because it has the ability to transport you, and it also holds energy, in a way. I work with oil paints, which are made from minerals, and I like thinking about paintings as relics or vessels of the artists. Every artist is like a wizard, and this is their magic.

You’ve had some powerful mentors, including the late Noah Davis, who founded the Underground Museum, and Jim Shaw. What did they bring to your practice?

Noah Davis was a huge influence on me. I feel like I started painting bigger after working for him. He was so inspiring because there was this need to always produce, not to think so much about what you’re doing, but just make something that day. There’s a certain ethic that he had about working and creating things, and ‘keep going and keep making things.’

So were you his assistant?

Yeah, I was in high school. I was like 17. The Underground Museum was not “The Underground Museum.” And Jim Shaw… I was working for [his wife] Marnie Weber. She did a seminar at CalArts, and I met her because I was a skilled technical painter. Jim Shaw is really inspiring to me too, with his collection of books, and his subject matter.

I was thinking about the Underground Museum and how it sort of democratized the LA art world. It was like this fusion of DIY spaces and the art establishment when they joined forces with MOCA in 2015. I’m wondering if you, having curated your first show, Veils, there in 2014, felt like, ‘wow, there is a place for me in the art world.’ Did you ever question your place or think about it in those terms?

I guess the only way that I think of making work or showing work is about who do I get along with? Who do I enjoy working with? That’s really important to me. Me and Jeffrey were friends for three years before I did this show.

Tell me about the process of developing the show. How fully formed a concept was The Emerald Tablet when you brought it to Jeffrey? Or was he just like, ‘Hey, do you want to do a show?’

He offered me a solo show. And then we both realized that that space is really large, like really large. And he asked me if I wanted to curate a show in addition to my solo show. At first I said, ‘no way,’ because I know how much work curating takes. It uses a different part of the brain than making artwork. But he very much believed that my work is not just my paintings, that it’s about a world I’ve created, and a universe. And he felt like that universe was really important to bring into the show as an extension of my paintings. So even though it was a lot of work, I couldn’t say no to that kind of opportunity. To make a universe and to use all my favorite artists that have ever lived.

Yeah, that is pretty much a dream scenario.

And the way that The Emerald Tablet was formed, after I chose the artists, I asked myself ‘what is the theme that connects them?’ That took me to metamorphosis, which then took me to alchemy. And then when I looked up alchemy titles, I came across The Emerald Tablet. From there I realized, ‘oh, that sounds like The Emerald City.’ And that took me down this rabbit hole of Theosophy and Los Angeles.

What is your relationship to The Wizard of Oz?

I think I had a similar relationship with it compared to every artist, where it’s one of the best works of art, and one of the first things that I saw that really blew me away and transported me. The Wizard of Oz is so embedded in our culture that I didn’t give it much thought until developing the exhibition. It was more of a way to weave a narrative between my work and a group show and connect my interest in Hollywood, the occult, and set design. It brought it all together.

So as a work of art it just resonated with you as something magical, and then you began digging deeper and you realized Frank Baum was a Theosophist. More was revealed, and then it just kept on revealing itself?

Exactly. I make constant discoveries, still, within it. And I feel like that’s where Carl Jung came in as well, where it taps into this collective unconsciousness. You know, with group shows sometimes you don’t get the piece that you had wanted, but it ends up working in the way that it’s supposed to. So I kind of just let the universe take its course on everything. We didn’t get Mike Kelley until three days before the show. I didn’t think it was even going to happen. And it’s the piece that brought that whole room together. It resonates with the Agnes Pelton’s landscapes so strongly that its uncanny. It all made sense in the end. Henry Dodger was obsessed with The Wizard of Oz. I didn’t even know that, but all of Frank Baum’s books were in his studio.

You did such a masterful job of weaving the Oz narrative through while letting the artists’ own voices shine. Those Leonora Carrington paintings couldn’t be more perfect; they feel like magical journeys.

I feel like the hero’s journey is very much in The Wizard of Oz. It’s why it’s a story that never gets old. It’s deeply rooted in archetypes and mythology, you know, going on a quest and conquering something, and returning to where you came from, changed. I’m really interested in the Luigi Ontani ceramic slippers because in the original Frank Baum, the slippers were silver. And that silver represents the color of the moon in Theosophy, of the astral plane. And so you put on the shoes, you enter the astral plane. I always liked the idea of shoes being a mode of transportation. And the Isabelle Albuquerque cat is based on Christina’s World, and she’s deciding which path to take. And Hugh Hayden’s ladder—it’s kind of like a ladder that’s going through metamorphosis. Even though his ladder is a tool it still has its challenges, just as the yellow brick road does.

Looking back on your last solo show, Unweave a Rainbow, at Vito Schnabel, I have to wonder—is there a rainbow connection? Because we’re sitting here in this rainbow portal room, and now you’ve created The Emerald Tablet, which literally takes us over the rainbow.

I know, and it’s weird because that show was named after a John Keats poem. It’s about how science was taking away the poetry and beauty of what a rainbow is, and saying to just accept the rainbow for its beauty. You don’t need to understand the rainbow, let it be. I think Theosophy is interesting because it blends science and religion; those two things can coexist. The divine exists in science and in reality. You can understand the science of a rainbow and still have it be just as mystical. It’s funny, because I know people think I’m really obsessed with fantasy, but I’m not. It’s all here, I just have a different perspective.

I’d love to talk a little more about Agnes Pelton, because she feels like such an important touchstone for the show. You ended up including four of her paintings, and creating a 3-D environment that essentially brought her vision to life.

I knew I had to create my version of the Emerald City, and Agnes Pelton doing a spiritualist landscape kind of felt like the right thing to do; I felt like she embodied everything I’m interested in. She was painting these paintings in Cathedral City, and her work is very much a blend of reality and her own imagination. There are these forms that look very similar to the Emerald City, and which look very similar to Mike Kelley’s “Kandor” and are also present in Unarius’ “Crystal Mountain Cities” film. So there was this shared vision of what a utopian city looks like.

So that beautiful green, airbrushed sky across the whole the back wall, did you paint that?

No, I got a scenic painter from Universal to paint that. There was a lot of outsourcing and I had a great art director who oversaw the production of that room. For the Unarius video, I hired someone to create the rock TV, and then the other boulders we rented and painted. The lighting was done by movie people as well. It was a perfect show for Los Angeles as it was very easy to get this all done here.

I think Agnes Pelton’s work is also such a blend of what I think of as Disney and spirituality—there’s a Fantasia element—which is my favorite aesthetic. This embodies the nature of Los Angeles where we question what’s real and what’s not real. Is it still magical even if it is a simulated experience? That’s why in that last room, you know, people really feel an energy. I wonder if it’s just done by theatrics, or the magic that exists in the work. So what I’m interested in exploring is, even if something is not authentic, is the experience you have valid? I believe it is.

I know those themes are also echoed by your suite of new paintings. Could you take us through the series?

Yeah, so the journey starts off with a black-and-white painting of an interior, and that’s supposed to be kind of like the beginning of The Wizard of Oz. There’s a woman who is at a threshold, and she’s entering or leaving that state.

She’s in bed, right?

She’s morphing into a bed.

Oh, so it’s kind of like entering the dream.

Entering the dream, yeah. And then the cave painting is called the Plutonian Cave of Eleusis. Basically, I was in Greece, and this psychic came up to me and she said that I was a cave goddess in a past life.

Which of course you already knew.

I’m like, “I thought so too!” Anyway, she told me to go to where the Eleusinian Mysteries took place. It’s an hour outside of Athens, and it’s this cave where there’s a hole to Hades, and Persephone would go between visiting her mother and visiting Hades through this cave. And there are still offerings to her there. So basically in ancient, ancient Greece there were whole tribes that worshiped Aphrodite and worshiped Persephone—and this cave where the Eleusinian Mysteries took place is where they also think the first psychedelics were ever taken.

Anyway, the painting is of my two best friends in the Waitomo Cave in New Zealand, which is covered in glow worms. It looks like you’re in outer space, but you’re actually in a cave. I really liked this interior, exterior energy.

Next it’s a bubble painting. I love the bubble painting because it represents the brevity of life but also very much exists in the The Wizard of Oz.

I looked at that and thought, the bubble is Glinda the Good Witch, but the red smoke is the Wicked Witch. Other people thought the smoke referenced Judy Chicago.

Right! It’s actually a postcard from the thirties or forties of Mount Vesuvius. And they had hand tinted the smoke to be rainbow like that. I love Judy Chicago, though.

After that is the painting of the chair inside the crystal. That’s very much related to traveling and ‘as above, so below.’ ‘As above, so below’ is the second verse of The Emerald Tablet, and it’s kind of what the show’s about. With the chair, I was thinking about what would be left over if there were none of us left. What’s the most human thing? And I was like, ‘The chair!’ It’s kind of an absurd human object, and it also has a significance in where your place is in the world, where you’re seated. It was just an intuitive thing to use the chair, but then I noticed on the cover of the Ram Dass book, Be Here Now, there’s a chair in this crystal form. And I was like, ‘Maybe it is about being present.’ And, yeah, chaos. The painting is called A Mellow Drama, and that’s totally Ram Dass. And also so LA; LA is the most mellow drama.

That last painting, The Tamed Beloved, is based on The Unicorn in Captivity, which is a medieval tapestry. I did a lot of research on that tapestry and the unicorn represents the Virgin. And it’s in a field where there’s a fence, but the fence is very low. And basically it’s allowed to escape, but it’s choosing to be captive. So it’s kind of like, wanting to be domesticated versus freedom. The series starts off with an interior and ends with an interior that is in color and she’s… maybe the female has become a unicorn.

She’s choosing to be tamed after this wild journey.

Exactly, yeah. She’s choosing that home, where she wants to be.

Have you lived in LA all your life?

Yeah, I have. I went to college here, I stayed here. I mean, I travel a lot—like during the pandemic I left for eight months. I went to Italy. I went to Cornwall. I had a whole adventure all by myself. But there’s no place like home!

THE END