Art that doesn’t make you think is just expensive decoration, and the work of Damien Hirst could never be accused of pretty vacancy. Like Warhol’s, Hirst’s art raises the Big Questions about life and death and truth and beauty, often all at once, with a deceptive simplicity that leads you to wonder if it’s art at all – which, of course, is the most provocative question that modern art can ask. Even those who actively dislike Hirst’s work are nonetheless validating it with their reactions: He got them thinking.

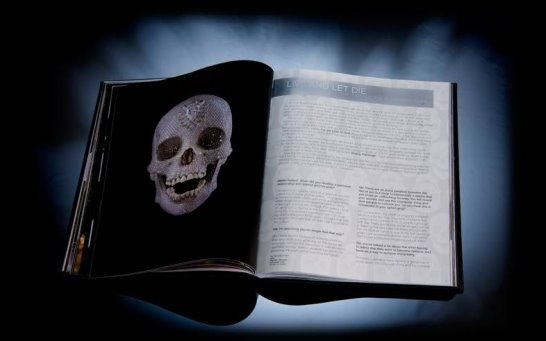

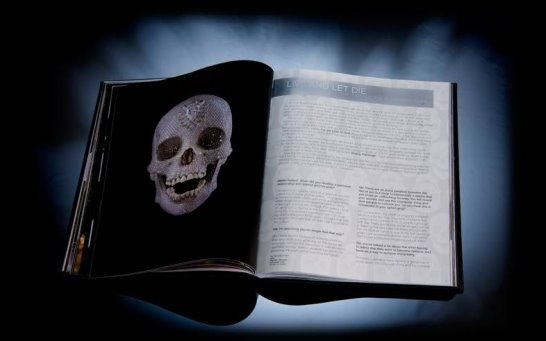

The winner of 1995’s Turner Prize and the onetime “enfant terrible” of British art, Hirst is now the world’s highest-paid living artist. His latest art world shake-up was the 2007 exhibition of a diamond encrusted human skull priced at $100 million; with an 80 million dollar difference between the cost of the diamonds and the price tag on the piece, For the Love of God dared to ask what determines the value of art, and many were outraged by his audacity. But if the value of art lies in its materials, wouldn’t a Picasso drawing be worth around 50 cents?

If we agree that the most meaningful art should serve society in some way, then Hirst’s most significant contribution has been the fearless way he reveals his own very human struggles. Dubbed “Mr. Death” by the British press, Hirst doesn’t slice a cow into pieces to gross us out; he wants to know what’s inside – what makes a living thing alive- while his recent Biopsy Paintings – lurid abstractions of cancer cells – dare to look at death close-up.

Now the father of three young sons, the 42-year-old Hirst has put his notorious hard-partying ways behind him, but he’s clearly still on intimate terms with the dark side. With bustling morning sounds filtering through in the background, the artist chatted by telephone from his home in England, discussing God, electric chairs, and the tombstones in his bathroom.

When did you develop a personal relationship with Warhol and his work?

I used to work at a gallery in London called the Anthony d’Offay gallery – I hung pictures in the back room – and I was there a couple times when Andy came in because he used to show there. I got to know him through that gallery. I kind of came late to Warhol. In the beginning I was more into the abstract expressionists – de Kooning and Rothko and those guys. I thought that was more pure; I thought pop art was a bit too close to the culture.

I’m assuming you no longer feel that way?

I think Warhol broke a lot more boundaries than any other artist, probably. All the things we associate with art that were kind of bad like fame, success, money…Warhol showed that you’re not inheriting the past, you’re inventing the future.

There are so many parallels between the two of you but most fundamentally it seems that you share an unflinching honesty. You will reveal your secrets and say the unpopular thing and dare people to criticize you. Do you think this is connected to your upbringing?

I come from the north of England, Yorkshire, which is a bit like that. They kind of believe that modern art is rubbish. A lot of people I grew up with say, That’s not bloody art! When you can do a drawing that looks like me that’s art. I remember my brother came to one of my first openings when I got successful and he said, if someone else fuckin’ kisses me I’m gonna punch them!

You’ve talked a lot about the artist having to admit that they want to become famous, and fame as a way to achieve immortality.

Yeah, I definitely think fame is a good way to avoid death. It’s a big, ugly thing and it’s unwieldy. You can’t control it. Fame and being an artist are quite difficult things to marry. There’s a lot of bullshit that goes with fame, and as an artist you’re supposed to clear away all the bullshit. I used to always watch famous people to see how they handled it. Honesty is something really important, I think, in art. You’ve got to be who you are. If somebody comes up to me in the street I always try to do a drawing for them. I think the moment you go, oh, fuck off, I’m not in the mood, it works against you in a really bad way.

There’s different kinds of fame for artists, and Warhol was probably the first famous artist that I knew of in that way. I remember when I worked at the gallery and he had his show. He said, We’ll only do the show if I get the whole top floor of Claridge’s. And I want 200 bottles of Coca Cola. And he just arrived with masses of people and just had a party the whole time he was there. It was like a rock star, and it was a really weird thing to think an artist was like that, ‘cause I was looking at Richard Long, this British artist who was doing these walks in the country.

So that sort of shifted your idea of what an artist was or could be?

Well, it’s very seductive as well. It’s like, you want to hang out with someone like that. Same thing for me with the Beatles when I was a kid. I got really into the Beatles early on. I was always drawing, but when I was at school I was definitely on the garage roof with a tennis racquet, pretending to be the Beatles playing really loud. I’ve often said that the Beatles have been more influential than Picasso and Miro. They were really inventing the future, coming from a similar background to me and had gone out into the world and dealt with all that fame and remained cool. That’s why Joe Strummer’s a great guy, cause he did the same thing: went to the top and didn’t take the money. When it became a choice between money or integrity they kept the integrity, which is an amazing thing to do. And then Warhol took it a step further and just went, the integrity’s not important. Which is a kind of integrity unto itself.

You once said belief in art is like a belief in God – do you still believe this?

I don’t believe in God, but I think in order to live you need belief of any kind. If you look at life like scientists do, using logic or rationality, then you can’t get out of bed in the morning. I think any kind of belief is the same, really. It’s just a belief that there’s more to life than there actually is. I definitely believe art is food for the soul, which is what religion is.

You call your office Science. Where does science fit in to your definition of art?

I think art can incorporate everything. I like the idea that art is like holding a mirror up to life. Something that keeps recurring for me is the fact that art, like science, comes as a kind of replacement for religion, offering new hope and salvation in a way that religion used to. When I was very young I went in the chemist and saw the pharmacy on the wall with the drugs bottles and people were getting these little pills, believing in them, taking them. They don’t question it. It’s that unquestioning belief that I always wish people had in art, so I then made the medicine cabinets from that. I just took it directly. I was trying loads of way to make art that was believable, and I didn’t realize that you just take something believable and you put it in an art gallery and it is art. That was a big breakthrough for me.

You have Warhol’s Little Electric Chair in your personal collection. What about it resonated with you?

It’s just an iconic image, isn’t it? Man’s inhumanity to man, especially with a bit of distance to it. It’s amazing that he did that in the ‘60s, and as time passes the painting’s gonna look wilder and wilder, because it’s just doesn’t make any sense. It’s like Van Gogh’s chair, it’s about absence. Like, with death you don’t need the horror, you can just see a guy’s hat.

This clothing collection is inspired by the intimate relationship with death that you and Andy Warhol have in common. Do you think that you view death in the same way that he did?

I think the similarities are superficial. With his electric chair, I think he was more interested in the celebrity of the electric chair than the horror of it. The horror is a byproduct. I’m more interested in kind of dark thoughts, I think, than celebrity. Everybody dies and it’s quite a personal thing, whereas Warhol’s is all newspapers, criminals, and a celebrity of death associated with it. I’m looking for something a bit quieter.

I heard that your home is decorated with old tombstones. Where did they come from?

Somebody offered them to me. I was trying to get flagstones for my house in Devon, and I work with a lot of antiques and reclamation people, and one guy up North just said he’s got some gravestones, and you could use ‘em upside down so you don’t see the lettering on them. I said, you’ve got gravestones? I’ll take em! I’ve had them for quite a few years now, and at the last minute I decided to put them in this house. It’s a very old house next to my studio, and we put them in the floor so that you can read them. Somebody said to me recently, Is the house haunted? And I said, It will be by the time I’m finished.

You have three young sons. Has fatherhood affected your relationship to mortality?

My relationship with death changes every day. I think as you get older you have more fear, more doubts. When you have kids it brings it into stark perspective, and you can’t put yourself first anymore. You know, I used to enjoy all the gory horror about death and murder and all that in the newspapers but you read about kids dying and it gives you the freaks, which it never used to do. But once you get kids it’s like, oh my god. You really feel those stories in a different sort of way, and it causes angst instead of excitement. But it’s not just having kids and suddenly your relationship with death changes. Really, every single day I’ve woken up my relationship with death is different.

In one interview you said that you hoped one day to just be able to be in the moment, to live.

When you’re beginning life you’re always judging yourself in terms of your parents, then in school you’re always looking at what you’re gonna be when you leave and it’s always based heavily in the future. Then you get into art school, and as artists we were talking about being famous, winning the Turner prize. There’s always something in the future that you’ve got your eye on. But if you look too far into the future then you’re gonna be in a wooden box in the ground. Its always nice to kind of pull back from that a bit and try to be here now.

That’s a pretty Buddhist attitude.

It’s not that religion is bad, it’s just the way it’s been used over and over again. If you sit in a dark room and think, you’re probably gonna come up with a religion, which is what happened in the beginning. I think all religions are just old, that’s the problem. Everything else that we’re in contact with has been redesigned for today. People are looking for belief, but they’re moving the goal posts, so it’s very difficult to believe in somebody who moves the goal posts. They’re kind of having to make it up on the spot, which is something else that doesn’t really tie in with belief. Trust me! I’ll truss you up like a chicken!

I read an article about your “Death of God” show in Mexico City in 2006, and you were talking about how you were more comfortable using skull imagery in Mexico because there they understand that the skull is a metaphor for transient life, whereas in England or America it just means death. What does it symbolize to you?

It’s just this remarkable image. No matter how hard you look at it you can’t believe that it’s you. I’ve been doing some paintings of skulls and you look at it and you look at it and you can’t believe it ever was a person. There’s that quote: Webster, they say, could see the skull beneath the skin. It’s something always there that you deal with every day but it’s beneath the skin. Skulls are everywhere, really. It’s where we’re all going. It’s always been popular in Mexico, but there’s probably more skulls in England and America right now than there are in Mexico. But no one’s facing up to death and it just becomes a comedy thing. I suppose at the end of the day with death you can only celebrate, because it’s so unknowable.

I thought it was amazing, looking over the collection, how some of yours and Warhol’s images – the human skull and the human heart in particular – fit together like two halves of a whole.

It’s weird, isn’t it? I saw the first collection that Adrian did in Fred Segal, and I bought the whole collection, I just thought it was great. And he contacted me after that and said do you want to do one together? And I was like oh, yeah. So I was kind of a fan of his stuff, and I just let him do it. He’s got great idea after great idea. And I just sign it. I love that.

Have you ever done anything with clothing before?

I’ve worked with Libertine – Cindy and Johnson are friends of mine – and we did some spin paintings on jackets for charity. And I almost did something with Hussein Chalayan in Paris but he wanted it to be art and I wanted people to be able to wear it, so it never really worked out.

This line is obviously wearable.

Yeah, I definitely want people to be able to wear it. Something that happens sometimes if you’re an artist, clothes designers come to you and then they want to make art. As an artist, especially when your prices are going high, it’s quite difficult. People that you gave things to when you were a kid are all selling them. You can’t afford to give your friends work. Even if you do they just sell it. So I think it’s good to be able to give people something they can afford. I made spinning surfboards for people, and they put them on the wall, they don’t ride ‘em. You start to feel like Midas.

You did an interview with Irvine Welch and you said, “I’ve always believed that art’s more powerful and important than money, but it gets fucking close sometimes.” Do you think this new work, “For the Love of God,” is your way of putting that to the test?

Yeah, absolutely. It’s been a big way of doing that, pitting one against the other, in as big a way as possible at that particular moment. It’s quite funny with that, the way the price tag always comes with it. You don’t get that with artwork. I was actually worried that it might just look like something Ali G might wear instead of something timeless, but in the end I think it works quite well. It’s an amazing thing. I actually tried to avoid skulls for a while, because they’re everywhere, and then I thought, I should just do it better than everyone else.