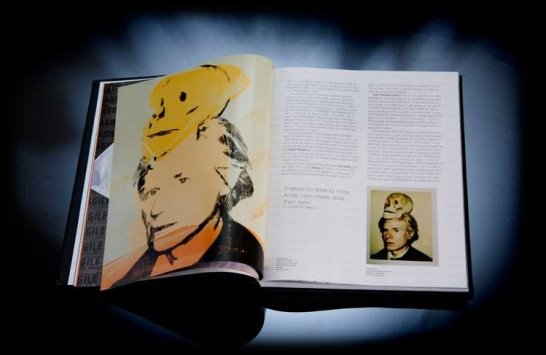

“Warhol is Dead!” proclaimed the posters for a group photography show in New York – just one blip in the blitz of books, articles, films and exhibitions that commemorated Andy Warhol’s death 20 years ago this past February. The gallery walls were hung with images of the artist, very much alive: Silk-screening bananas at the Silver Factory; posing with Nico and Candy Darling; snapping his omnipresent Rollei; sightseeing in Paris; pumping iron in his personal gym; visiting the Bronx Zoo; clubbing with Basquiat; planting a kiss on John Lennon’s cheek. Warhol’s wig gets shorter, darker, longer, lighter, spikier; his smiles are friendly and unforced; and in 1982 he looks surprisingly buff. Only five years later he would die in New York Hospital at the age of 58, the victim of negligence.

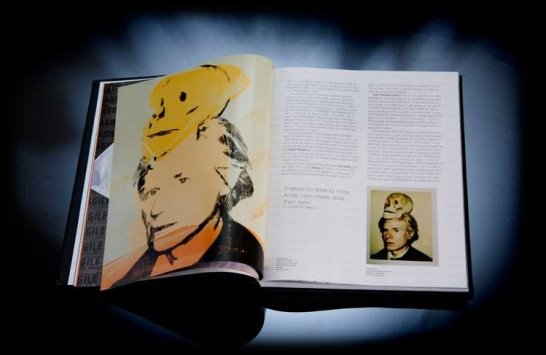

Christopher Makos, who captured the Lennon moment and other private glimpses of the man he befriended in 1976 and continued shooting until the end of his life, says that these days he’s often asked if he misses Andy Warhol. And does he? “Are you kidding? There’s no time to miss him! He’s more alive than ever.”

It’s undeniable: Two decades since he was laid to rest near his mother in a cemetery just outside Pittsburgh, we are living in Warhol’s world. His wigged visage is as recognizable as the icons he enshrined in canvas and paint: Marilyn, Elvis, Liz, and Mickey Mouse, and his art continues to fetch record prices at auction (in May, 1963’s Green Car Crash sold at Christie’s for $71 million). Yet it’s Warhol’s oft-quoted prediction, “in the future everybody will be world famous for fifteen minutes,” that might even be his magnum opus. This off-the-cuff remark from 1968 has so thoroughly insinuated itself into our cultural DNA that to the YouTube generation, it sounds less prophetic than fundamental.

Many have tried to get inside the enigma wrapped in silver foil that is Andy Warhol – hailed as a visionary, dismissed as a fraud, called an American treasure, a great artist, a non-artist – but it’s actually in his shiny reflective surface that Warhol’s true essence is revealed. When we look at the work of this self-described “deeply superficial person,” we don’t just see a movie star or an electric chair. At first we do, but then these pictures begin to tell our own stories back to us – our deepest desires and fears and our collective history encapsulated in each symbolic, almost hieroglyphic image.

“Wham! One second, it’s in,” says Ric Burns, who directed the PBS American Masters documentary Andy Warhol that aired last fall. “But why don’t you just go away? That simple thing is like some strange sort of plastic artistic figment that begins to unfold like an origami flower inside your head. Suddenly it becomes deeper or philosophical or you begin thinking about yourself.”

Warhol once said, “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface: of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

Critics took the statement to mean that he had no depth, that he and his work were hollow. But interpreted from another angle, what Warhol meant was that he had no hidden agenda; there was no message the viewer was supposed to “get.” He left that part up to them. Warhol rejected the idea of editorializing, striving instead to be a blank slate, a mirror of his times. Being that mirror required him to banish any fragments of “self,” and if a person looking at his paintings saw nothing more than what they had for lunch, fine. Warhol would be the first to admit that his subjects were ephemeral – disposable, even. He once described Pop Art as “liking things,” and in his characteristically democratic manner he didn’t discriminate between a goddess of the silver screen and a bottle of Coca-Cola.

Burns’ film details the moment Warhol had his Pop breakthrough, rendering a bottle of Coke with the clean lines and flat color field of a printed image, abandoning the painterly brush strokes of previous versions. He invited some friends to come see the work, including the curator Henry Geldzahler and the filmmaker Emile de Antonio. The group unanimously preferred the slicker version, de Antonio enthusing, “It’s naked, it’s brutal, it’s who we are!” Talk about the real thing.

For Warhol, at one time the most successful commercial illustrator in New York, the struggle between art and commerce didn’t exist. He was enthralled with mass produced imagery, from movie magazines to advertisements to labels on food in the supermarket – and why not? This is the most popular art in the world. When asked by a journalist why he chose to make copies of things instead of painting something new, Warhol responded, “It’s easier.” But that doesn’t explain how or why his art transcended the vernacular, or why it’s lasted.

Art critic Dave Hickey believes that Warhol, a devout Catholic who went to church every Sunday, recognized in American culture a certain relationship to images – including brand logos – that was comparable to the worship of religious icons in a church, where the representation itself is regarded as sacred. “Soup cans and Elvis and Marilyn actually function as icons in the culture,” Hickey theorizes, “as embodiments of values rather than just pictures of values.” In turn, he adds, “these icons provide the objects around which we organize our lives.” Mass production allows for a cultural “discourse of objects” that transcends place. “If I move to Portland I’m still gonna be able to talk about Campbell’s soup and you’ll understand.”

Warhol also understood the American consumer’s obsession with choice, which is why he hand-painted all 32 varieties of Campbell’s soup, a collection that sold for $1000 in 1962 and is estimated to be worth well over $100 million today.

The introduction of the silk-screening technique into his work that same year brought the artist ever closer to his professed desire to be a “machine.” He opened the first Factory in 1964, producing plywood reproductions of Brillo boxes as well as cartons of Kellogg’s corn flakes and Heinz ketchup. As Burns notes, “The final joke is that they looked like mass production but they weren’t mass production. Everything is mediated. Don’t talk to me about ‘the hand is removed from his art.’ The ink is pushed through the screen by hand. An artist is there.”

Equally important is the idea behind these acts of appropriation: art is whatever you say is art – which continued in the tradition begun by Duchamp and has been carried through to the present by artists like Damien Hirst. Many people point to the Brillo boxes as the point that the trajectory of art as we knew it just came to an end. Warhol said it once and for all: art no longer was based on the traditional criteria.

Burns holds up Warhol’s films like Eat, Kiss, and the five-hour long Sleep, in which “human reality unfolds at almost pornographic closeness” as works that further extended the permission he gave to other artists. “He puts a camera on a still tripod, and that’s art? It raises the bar as high as you can possibly imagine.”

The Chelsea Girls, shot in the summer of 1966 and given a week-long run at MoMA this year, was almost proto-reality television. There was real sex, real drugs, and real rock ‘n’ roll going on in the film that was described by critic Rex Reed as “about as interesting as the inside of a toilet bowl.” In fact, the impact of seeing real people doing real things was so provocative – and so shocking – that the FBI actually followed Warhol around for a time, fearing that his work had the power to undermine certain traditional, conservative ideologies.

The persona Warhol cultivated during the mid-‘60s Factory era is the lasting image most people have of him today: a voyeur and a provocateur in a leather jacket, a striped tee, skinny black Levi’s and dark glasses. The icon-maker had himself become an icon, and with the rich, glamorous party girl Edie Sedgwick as his sidekick and a coterie of artists, drag queens, drug addicts, intellectuals and rock musicians orbiting his silver circle, he was primed for the media age. Warhol expertly fed the blossoming cultural obsession with celebrity and fame, offering three-minute screen tests and the possibility of “superstar” status for those who would open their souls to him and his camera. There’s no question that the man given the nickname “Drella” – a combination of Dracula and Cinderella – had engaged in a dangerous give and take with the people who streamed in and our of his life.

Those who took the promise of fame too close to heart included Valerie Solanis, a deeply disturbed writer who shot Warhol in 1968, telling police, “he had too much control over my life.” The author of an anti-male rant called the S.C.U.M. Manifesto, Solanis called Warhol that Christmas and told him she would shoot him again if he didn’t get her an appearance on the Johnny Carson show. “It was entirely the most Warholian moment in his whole life,” says Burns of the shooting. “How much more reality can you take in?”

In the hospital, Warhol was pronounced clinically dead for a minute and a half, and some would assert that he’d sensed it coming. As a sickly child he’d spent months at a time bedridden, and he certainly never hid his fixation with death. Even the beatific Marilyn paintings, begun the month she died, were conceived as part of the Death and Disaster series. In 1963, the same year he did his first society portrait of the collector Ethel Scull, Warhol was painting the electric chair that was used to execute Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, as well an image of a beautiful, anonymous suicide whose body is gracefully held in the hood of the car that broke her fall when she jumped. Later paintings of skulls and crosses reflect a more philosophical perspective on mortality, and the very last series Warhol did before he died following routine gall bladder surgery was the Last Supper paintings – over 100 variations on a common, mass-produced picture. Again, it makes one wonder if he wasn’t tuning in to some sort of premonition.

Even his champions believe that Warhol’s art stopped breaking down boundaries after the shooting in 1968; however his prodigious output never let up. Witness the Warhol Foundation’s efforts to compile a Catalogue Raisonne: in 20 years they still haven’t gotten past 1969. Warhol always continued to seek new outlets of expression and new business ventures, launching Interview magazine in 1969, publishing books, buying property in Montauk (asserting that “land really is the best art”), creating cable TV shows, and collaborating with a new generation of artists including Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat. His ‘70s and ‘80s portraits were a savvy, lucrative extension of the Warhol brand, and we can only imagine where he might have taken things in the ‘90s – The Factory Hotel? Air Andy?

Somehow it feels fitting that Warhol died before the explosion of the digital age – before mechanical artists and half-tones were made obsolete by desktop publishing; before Polaroid went out of business; before email and scanners and myspace. He saw it coming – and you could even say he made it happen, but it’s comforting to imagine him, still gossiping on a black rotary dial telephone, his camera loaded with film, filling his time capsules with paper, objects and icons.

Warhol once said that wanted his grave marked, simply, “figment.” It wasn’t necessary for his life to be memorialized with a big stone monument; his work would do that for him. Meanwhile, the artist was content to live on as that made-up invention, that fantastical idea, in your imagination.